An award-winning author with a strong focus on New Zealand and Maori history, Joanna has written a wide range of books including young adult, non-fiction and picture books. She also works as a consultant researcher, writer and editor on interpretation projects.

Please click on the book for more information.

Some titles are available for purchase.

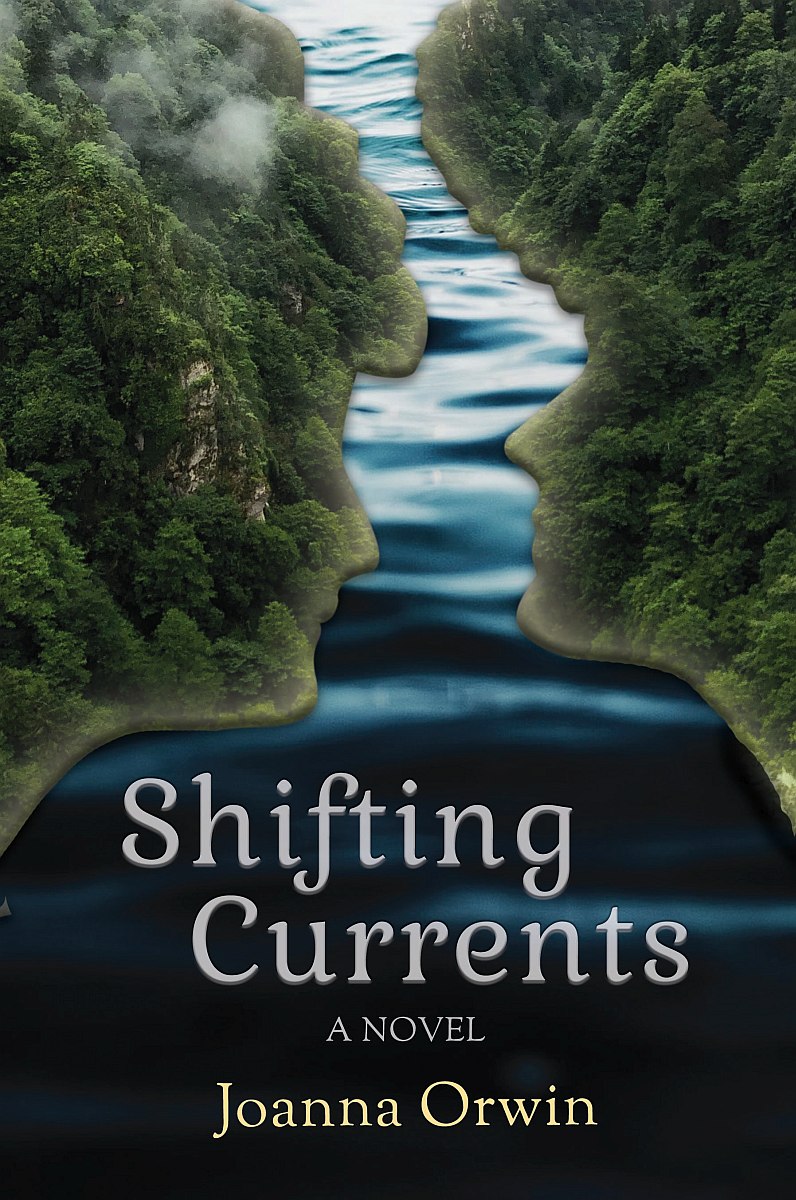

(Publisher Joanna Orwin 2020)

It is 1853. Previously widowed Lydia Boulcott has remarried, hoping to escape her shameful past. The isolation of a new life in the kauri forests of New Zealand’s far north offers the chance of a respectable future for her and Hannah, her five-year-old daughter. To her dismay, Lydia finds that one of her few neighbours is none other than ambitious Eliza Noakes - someone from her past capable of ferreting out her guilt-ridden secret. Despite Lydia’s determined efforts to avoid Eliza, fate constantly throws them together ...

Inspired by the intertwined lives of two real women, this historical novel is set against a vivid background of hardscrabble pioneer life in the remote Kaipara at a time when New Zealand’s cultural and natural landscapes were rapidly changing.

(HarperCollinsPublishers 2009)

Different cultural perspectives on Marion du Fresne’s fatal encounter with Bay of Islands Maori in 1772 are seen through the eyes of participant André Tallec, a young French ensign, and his counterpart Te Kape, favoured protégé of prominent chief Te Kuri.

...builds up the tension and in reading it you feel part of this ball rolling towards an unstoppable disaster.

Vanda Symons blog 2009

In a superb retelling of a collision of cultures doomed to end in tragedy, Joanna Orwin cleverly interweaves Maori and European perspectives, providing a vivid and compelling tale of loyalty, friendship, bloodshed and revenge from the age of encounter - when European and Polynesian first measured each other face to face.

Wheelers 2009

...by interspersing French and Maori interpretations of events she [Orwin] captures the greatest tragedy of this encounter; the fact that each party was acting with the best of intentions.

Otago Daily Times 2009

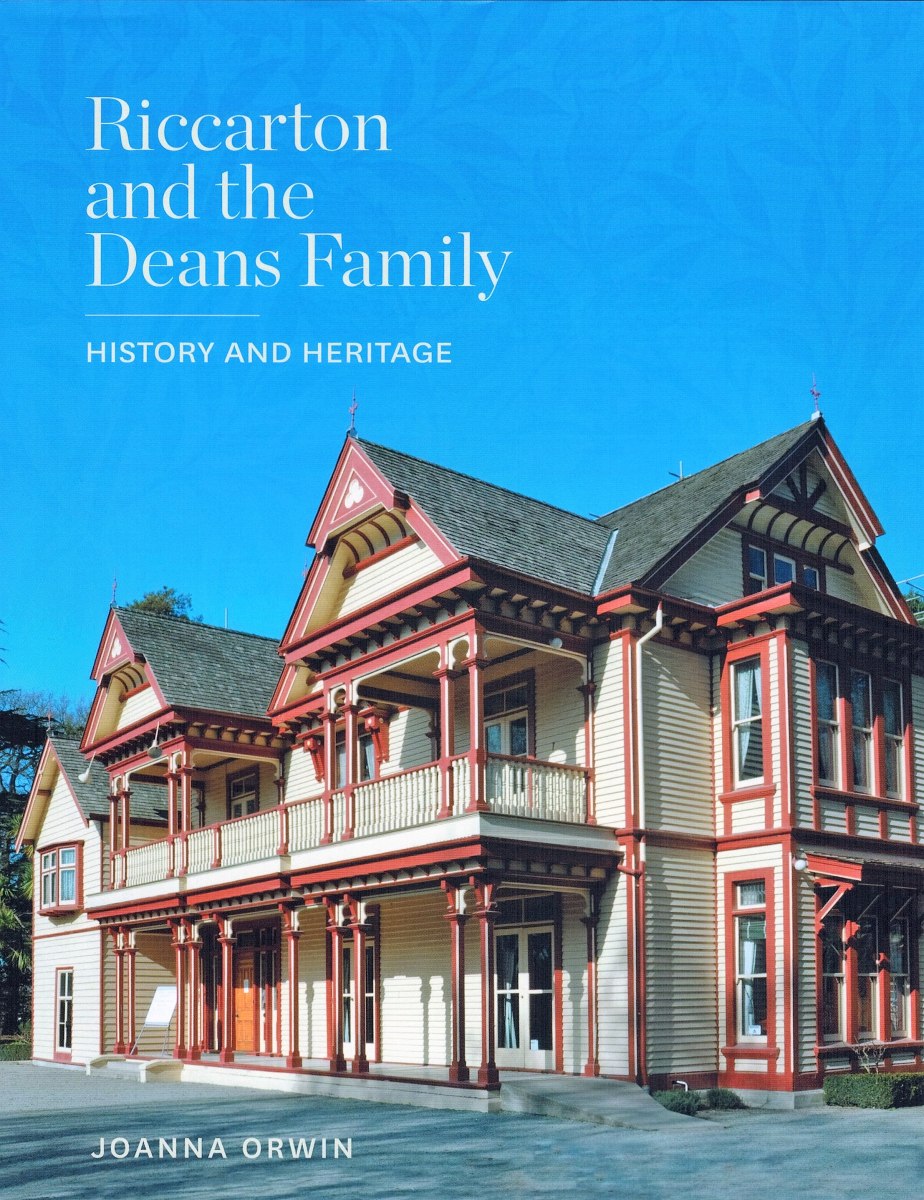

(David Bateman Ltd 2015)

The story of the pioneer Deans family encapsulates the natural and social history of Canterbury, centred on the sole remnant of ancient floodplain kahikatea forest, preserved as Riccarton Bush and gifted to Christchurch city in 1914. This book re-examines the history of the family at Riccarton and updates the subsequent restoration of the bush and the two historic houses associated with the Deans family, including the major repairs to Riccarton House needed after the 2010-11 Canterbury earthquakes.

a well-researched, perceptive and richly illustrated account that doesn’t avoid rattling the occasional skeleton in the family cupboard... elegantly written.

Listener 2016

Award-winning author Joanna Orwin encapsulates the natural and social history of Canterbury in this important book.

Beatties Book Blog 2016

(edited by Tessa Duder)

Expedition to the Boulder Bank

Pp 229-237

Two girls set out on a weekend adventure, rowing their boat over to Nelson’s Boulder Bank for an overnight camp. After setting up camp, they go for a sail, without realising the tide is already on the ebb. This is a true story, based on my childhood years of mucking about with boats.

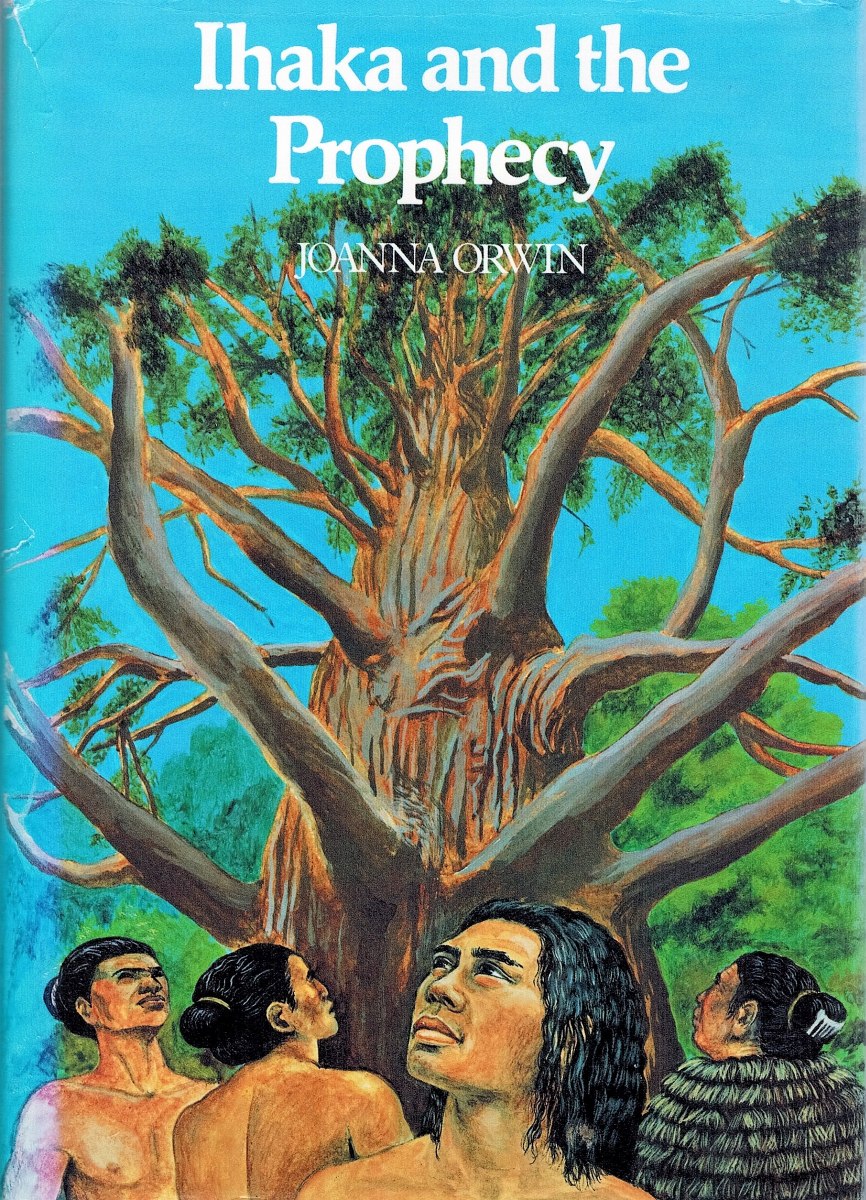

(Oxford University Press 1982)

Set in the earliest period of New Zealand Polynesian history in the vicinity of Delaware Bay, Nelson, this story follows Ihaka and his friend Pahiko during the summer bird hunting season.

A delightful story, enriched by the author’s knowledge and love of our native bush, and her interests in archaeology.

Christchurch Star 1983

The 12-century Maori setting of this story breaks new ground in New Zealand fiction for children… Much anthropological lore is woven naturally into the narrative, but the action moves swiftly and the reader becomes involved with the characters...

School Library Review 1984

Enthralling tale of Ihaka’s forest travels…both touching and full of suspense. It is a difficult book to put down.

The Press 1983

Joanna Orwin has imaginatively reconstructed the Maori world of the12th century...bringing it vividly alive for nine to 12 year olds, It is [her] achievement that she has written an exciting story which coheres, in which events of later chapters develop naturally from those that precede them.

NZ Listener 1983

(Oxford University Press 1984)

Apprenticed to Paoa, tohunga in wood and stone crafts, for the building of a double-hulled canoe, Ihaka grows to manhood.

An enjoyable, imaginative reconstruction of the early days of people in our country. School Library Review 1984

An impressive sequel…Not only children but many adults will find Orwin’s narrative satisfying in its portrayal of a prehistoric community unified in a complex undertaking.

NZ Listener 1984

A story that is fascinating and appealing on several levels...

Evening Post 1984

Excellent insight into Maori traditions... Ihaka and the Prophecy has the ring of authenticity. Wairarapa Times 1984

(Scholastic 2007)

Based on a true story, Laura Ann’s fictional diary tells of her adventurous life as a bush cook’s offsider in the 1920s logging camps located in the kauri forests of the Kauaranga Valley, Coromandel.

Deeply personal and engaging, the book presents a lifestyle that was unique to its time – a valuable and enjoyable read for younger audiences.

NZ Memories Oct/Nov 2007

The diary provides lots of fascinating social history... as well as a good picture of life in bush communities and camps. There are some hair-raising accidents and mishaps, even deaths, as well as richly detailed accounts of the interesting events of daily life in the 1920s.

Magpies May 2007

Joanna Orwin’s in-depth knowledge of the kauri timber industry provides considerable detail to this fictional diary. Although Laura is a fictional character, Joanna Orwin’s interviews with 93-year-old Ruth Murray have provided a unique and authentic voice... A valuable addition to a well-respected and popular series.

Magpies 22, July 2007

This is a most appealing book in every way.

Beatties book blog

(New Holland Publishers NZ 2004, Edition 2, 2007)

Kauri trees, timber and gum played an important role in the lives of northern Maori and later European settlers. An account of the cultural and natural history associated with kauri from the time of first settlement of New Zealand through to modern conservation efforts.

This superbly presented slice of our national history is a certain winner... Orwin combines the awareness of an historian, the perception of a novelist and the understanding of a scientist with her depth of knowledge of things Maori... Kauri is a book worthy of its subject.

The Press 2004

(New Holland Publishers NZ 2019)

New Zealand’s giant native conifer, the kauri, once dominated the northern landscape, looming large in the lives of the country’s first inhabitants and the later European settlers. Over the centuries, kauri’s high quality timber has yielded war canoes, ships’ spars, furniture and houses, and the industries that sprang up around it had a defining impact on early New Zealand society. Today, though the kauri forests are a shadow of their former selves, their legacy lives on in New Zealand’s rich cultural inheritance, and the tree still towers over us, commanding respect.

Now, in the twenty-first century, at the same time that northern communities are rallying to restore the health and biodiversity of the remaining kauri forests, a new plant pathogen is killing kauri trees throughout their natural range. This revised and updated edition shows how the ongoing story of kauri continues to encapsulate the story of New Zealand in the challenging environment of our modern world.

(Edited by Jessica Adams, Juliet Partridge, and Nick Earls)

Shadow dance

pp 563-575

Scott’s discovery of an ancient Maori back pack up amongst the linestone outcrops leads to nothing but trouble. He hasn’t told anyone he removed a small stone carving, which he has hidden in his sports bag. When he tries to return the carving, it is too late to avert his fate. The shadows from the outcrops are waiting for him.

This story had the same trigger as my 2001 novel Owl – the discovery of an ancient Maori kete in an area of limestone outcrops, but has a more sinister fantasy element.

(Longacre Press 2004)

Great-grandmother Gi-Gi shares entries from her Shetland ancestor’s diary written on 1870s Stewart Island to help teenager Jaz deal with the parallel problems she faces in a modern world.

Both 19th century Stewart Island... and 21st century urban NZ are powerfully evoked in this double-voiced story about growing up and fitting in. A wonderfully researched page-turner.

Canvas, NZ Herald 2004

This is a cleverly woven tale, where fact and fiction are intertwined into a believable whole. From modern day New Zealand and back to pioneering times, it is written with sensitivity and skill.

NZ Writer’s Ezine 2005

Unpretentious, yet deftly in tune with both the past and the present, Out of Tune is an absorbing and rewarding novel.

Magpies November 2004

...the book appeals as much to adults as well as to its target audience with its vivid story of the struggles for existence in early New Zealand and portrayal of the pressures faced by young people today.

The Press November 2004

(Longacre Press 2001)

Set on a high county farm in limestone country, where Hamish (Owl) and Tama have unwittingly set free the force of Pouakai, the man-eating eagle of Maori myth. They must defeat Pouakai to save themselves, Owl’s family and the local farmers from the eagle’s depredations.

It is sometimes difficult to find fiction for young teenage boys, something that will grip their imaginations, hold their interest and has appropriate cultural touch stones. Owl is spot on...

A ripping read.

Bay of Plenty Times 2002

It shares with her previous novels, but much more compellingly, the hallmarks of quality and integrity, employing convincing detail to underpin leaps of imagination and weaving contemporary life through legendary demands.

Magpies 2002

Owl indicated a change in the direction of New Zealand children’s literature... Owl is notable because it shows that contemporary social problems can be depicted in a convincing story that also offers adventure and fantasy.

Story-Go-Round 2002

The novel’s action-packed plot, with its tense drama, is a strong point... Sweeping the reader along with the fast pace and a pressing sense of dread.

NZ Books 2002

(Summit Road Society 2008)

A guide to recreational activities on the Port Hills above Christchurch, with background natural and historical information.

(HarperCollinsPublishers 2011)

Several generations after volcanic eruptions and tsunamis caused the onset of the Dark, Taka is one of the Travellers chosen to venture across the Pacific on a sacred voyage in search of new resources to sustain the tenuous communities surviving in the far north of New Zealand.

Meticulously researched and beautifully crafted. ...Taka’s ultimate sacrifice is stunningly satisfying.

Listener 2011

...a richly-imagined novel, with convincing and likeable characters, forced into an impossible situation. ...a tale of courage, endeavour and belief.

Magpies 2011

...a science-fictional rewind of the ancient voyages which brought Polynesian settlers... to Aotearoa... Orwin’s post-apocalyptic society has complexity and a plausible range of competing viewpoints among its people. ...a thought-provoking young adult novel...

NZ Books 2012

...an absorbing and thought provoking adventure set in an unfamiliar future.

Tomorrow’s Schools Today

(Otago University Press 1997)

A descendant of an influential Moeraki Maori woman and a European whaler, fisherman Syd Cormack developed a lifelong interest in southern Maori history and the associated issues of land and genealogy. His memoirs and accounts of Maori history were recorded on tape at his home in Tuatapere when he was eighty-five.

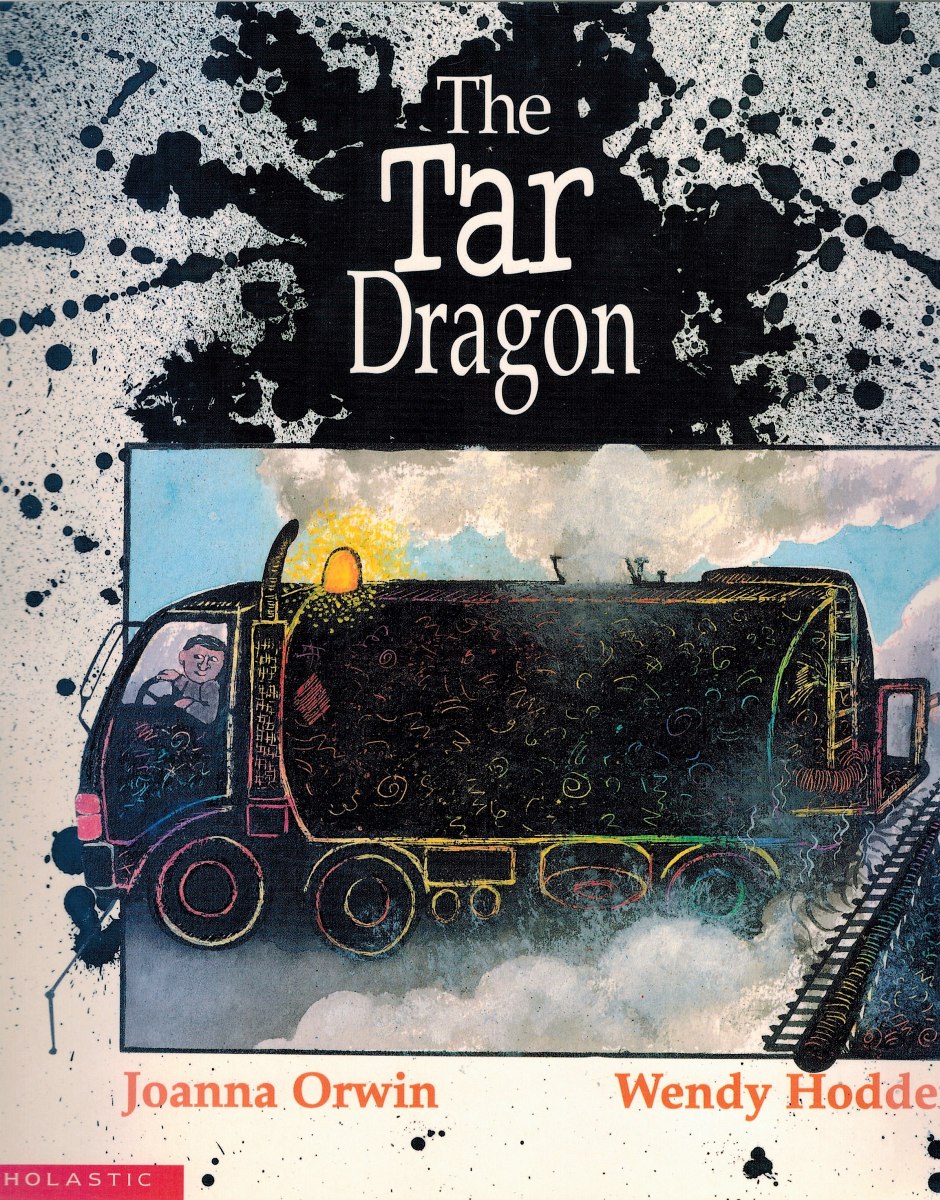

(Scholastic 1997)

A curious child encounters men spreading tar on the road, with the inevitable consequences.

As well as an effective twist to the conventional idea of a dragon, novelist Joanna Orwin uses “I was careful not to get too close” as her refrain in her evocative first picture book, The Tar Dragon.

NZ Books 1997

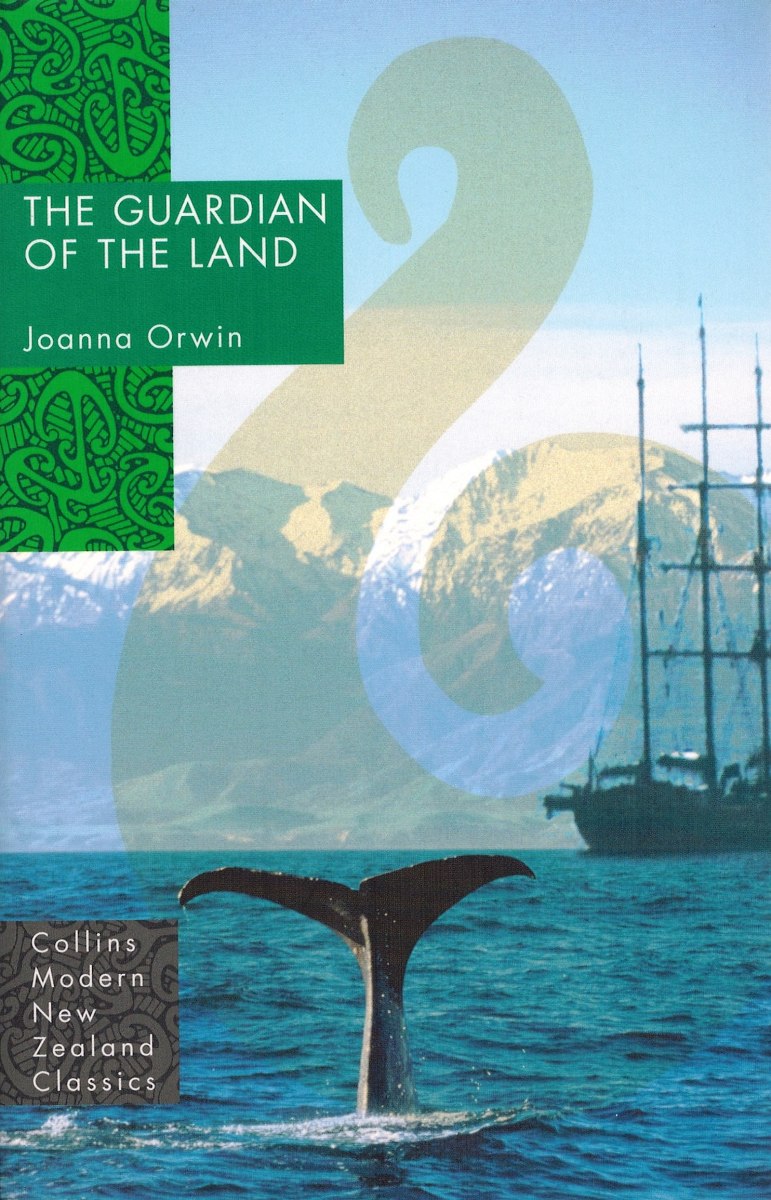

(Oxford University Press 1985, Ashton Scholastic paperback edition 1990, HarperCollins Publishers Collins Modern New Zealand Classics 2005)

David is sent to Kaikoura to recover from a long illness. His growing friendship with local boy Rua involves him in a series of adventures back through time to find the long lost pendant known to local Maori as the guardian of the land.

Whether David has experienced time travel or a series of visions is left to the reader to decide, but the history is richly detailed and convincing.

Magpies

This is an exciting story which picks up as the reader is drawn into the challenges… Orwin has written a compelling tale based strongly on the New Zealand landscape.

Wanganui Chronicle December 2005

Orwin’s deep knowledge of history and science are reflected in this richly detailed novel. First published 20 years ago, its message remains tireless. Respect for the land, its past and its power, brings Maori and Pakeha together in a lively conclusion.

The Press September 2005

Joanna Orwin in The Guardian of the land is so convincing in detail that she compels belief….The story impresses by its sympathetic treatment of prejudice and conflict, both tribal and racial.

NZ Listener 1985

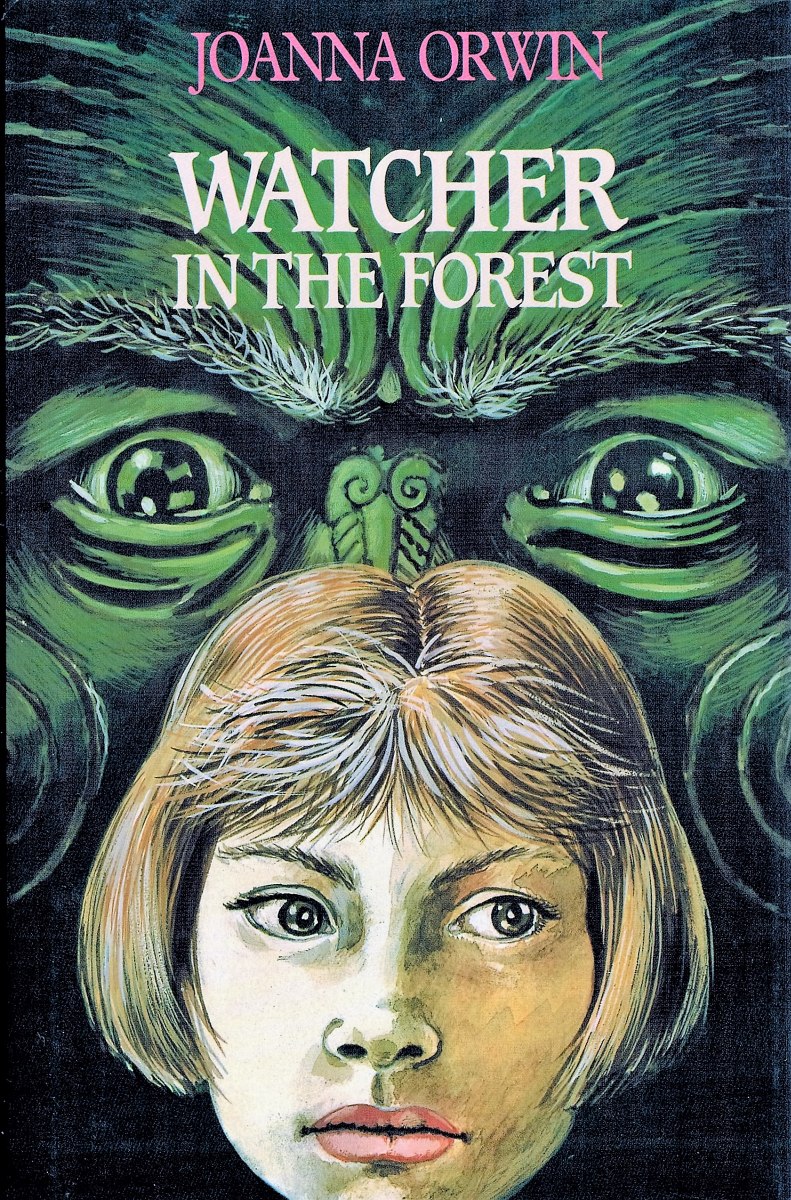

(Oxford University Press 1987)

Jen and her two siblings encounter a mysterious Maori figure in the bush on their first tramp without their parents. Under his influence, Jen’s visions draw them further and further into his world to assist in the recovery of a piece of greenstone.

Written by one who knows the bush and obviously loves it, this is a remarkable book.

Timaru Herald 1988

The mountains, the bush, the landscape and its changes wrought by flood and earthquake, are all strongly evoked…. Consistent and assured in its detail, atmosphere and at times reflective mood.

Listener 1988

Watcher in the Forest has just the right amount of suspense to keep the reader flicking over the pages

The Wairarapa Times-Age 1988

(Travis Wetland Trust 2005)

A practical guide providing background historical and natural information and detailed site explanations for a walk in Travis Wetland Nature Heritage Park, a major wetland restoration project in eastern Christchurch.

(Edited by Kate De Goldi and Susan Paris)

Seeds

Pp 54-64

This commissioned story is set in Christchurch’s Botanic Gardens in 1875. Harriet has been helping her gardener father in the potting shed when the Curator takes an interest in her. A job as a maid in the local vicarage awaits her, but after helping the Curator to sort seeds she has set her heart on continuing to work with plants.

An interview with Barbara Murison for Around the bookshops 2001

BM: My first introduction to your books was when I read Ihaka and the Summer Wandering as a serial to a group of children as part of a week long holiday reading programme. This was your first book, wasn¹t it? It, and all your books since (except for your fairly recent picture book) have focused on the New Zealand landscape and on Maori myths and legends. Has this been a lifelong concern and interest of yours? Your latest book, Owl, involves the legend of Pouakai and again reverence for the land and for family roots. Would you like to talk about the book and how it came about?

JO: Landscape and its power to move and influence people has always been something that has intrigued and provoked me. Stories that used the power of place to create atmosphere and authenticity had most impact on me as a child – and still do. As I grew older I became interested in the natural processes that form landscapes, and ended up studying geomorphology (the science of landforms) and botany at university. This led me into a job as a plant ecologist – one of the main attractions was being able to spend time in the mountains. So, when I came to write fiction, it was a natural progression to try and recreate an authentic and evocative landscape and people it with characters who were strongly influenced by that landscape. I wanted to write about New Zealand, so choosing prehistoric times seemed appropriate (not that it was a conscious choice really – this is all hindsight reasoning!). In that first book – Ihaka and the Summer Wandering – I was definitely trying to emulate Rosemary Sutcliff as a role model – a wonderful writer and one of my favourites.

The Maori focus was of course part of that. We’d been taught that Maori came on the Great Fleet in 1350, so the discovery of a moahunter quarry site on the Whangamoa Hill when I was about 10 or so, which I was taken to see, had a huge imaginative impact on me – a thousand years of history and this tiny quarried outcrop and its workings tucked away miles from anywhere in what would have been dense bush. Raised all sorts of questions – how did those early people find it and why; what was it like to live then. That impact was powerful enough to trigger the Ihaka stories 25 years later. It was a chance to try and answer those questions.

But it wasn’t until I wrote Watcher in the Forest that I had the courage try something that was more imaginative and involved something of the power of Maori myth and symbolism. Although The Guardian of the Land used timeshift, it was still very much a factually based story, drawing on real archaeological discovery and historic detail – props I needed really. I was very aware that I didn’t at that stage have the knowledge or understanding to go too far down the track of myth and legend, but it was something I wanted to do eventually. Alan Garner’s The Owl Service was definitely an influence there, as Red Shift was for Guardian (funny – I’ve just seen the connection with Owl as my title).

So Owl is my attempt to use a myth as the basis of a story, as a metaphor for what is happening to the MacIntyre family. I was trying to use myth in a modern context, but using it the way it’s always been used – as an explanation and pattern for human behaviour.

This story has had a long gestation. The trigger was the finding of a 500-year-old woven flax bag on a wooden frame by a friend of mine more than 15 years ago. Tucked away on a ledge amongst fantastically shaped limestone outcrops, its Maori owner had obviously intended to return for it, but never had. Over the years, other things built onto to that starting point – translating the Pouakai legend from a nineteenth century Maori text (as part of a university paper on South Island Maori) was one – also associated with limestone country in some versions. Then I had an outline of a high-country farming story that involved city girl-country boy, originally commissioned as a film script that never got off the ground. The rock drawings are another aspect of the first inhabitants that has always intrigued me – again set in that limestone landscape. So when I began writing fiction again, all this stuff came together to give me the raw ingredients for Owl.

BM: There is a difference of 16 years between the publication of The Guardian of the Land which was the 1986 Children’s Book of the Year and Owl. Do you feel there are issues you would address in a children’s book now that perhaps you mightn’t have felt comfortable doing in 1985?

JO: Most definitely – coming back to books written for New Zealand children after a long break meant I became very aware of how much has changed. The boundaries all seem to have gone, certainly in books for older children. I have some reservations about this. I suspect kids don’t always want to be reading social realism of the tough kind, having their noses rubbed in what they’re often already facing in their own lives. Books can be a wonderful way of escaping from life. Then again, books that tell a child he or she isn’t alone can be a great comfort – but they must be a good read as well.

BM: Sixteen years is a long time in a writer’s life but does this mean you haven’t been writing at all in this time? How long were you working on Owl?

JO: Well, it’s 14 years since Watcher in the Forest. A long time indeed. Initially I had decided to opt out for a few years, finding writing fiction and going back to work part-time as a science editor didn’t prove that compatible – too much involvement with words. I had hoped to come back to it when my youngest, Kate, started high school. But it wasn’t to be. First my mother died, then my husband. Writing ended up very low on my list of priorities, and it wasn’t until my three kids were independent that I was able to even think about it. I did write some other stuff in that time – 20 odd science feature articles for trade magazines at one stage, and a major commitment to an oral history project I did for the Maori Department at Canterbury University, which ended up in book form as Syd Cormack’s memoirs Four Generations from Maoridom (University of Otago Press).

After so long, it wasn’t easy taking the plunge, leaving paid employment and trying again. I had a lot of support and encouragement from my now grown-up family though – without that I probably would have chickened out. Owl was the focus when I left work, and I had been mulling it about in my mind for some time – it had been spasmodically rising to the surface for a year or two, once I had decided I would eventually try writing again. The book took me a year to write once I sat down and started properly – it’s taken Longacre over two years to publish it, so that’s an added time lag.

BM: One of the very noticeable things about all your work is the authenticity of the way families live and react and the way in which the children and teenagers speak to each other. Are you in constant touch with this age group?

JO: What music to my ears. I’ve always thought other writers were very much better than me at achieving that – Margaret Mahy of course, Tessa Duder and William Taylor (and now more recent NZ writers like Paula Boock, Kate de Goldi, Fleur Beale, and Bernard Beckett, to name just a few). It was one of my major concerns about coming back after so long – being out of touch with children and teenagers, for I don’t have a lot of contact any more. I read teenage magazines a bit – Tearaway mainly, listen to kids as they pass me on the street. It’s more attitude and style than actual current teen speak, and I think that doesn’t change so much. I guess for the family stuff I still draw very much on my own experience of being that age, and on my observations of my own kids and their friends when they were younger – they always accused me of putting them in my books, though it’s never direct. There’s more bits of me in my characters than of them.

BM: When you are writing do you have a particular audience in mind or is the story the important thing?

JO: Always the story. Obviously the way I choose to tell the story is influenced by its target audience – I’m not writing for adults after all. Audience would affect tone, depth, pace, but not language – I don’t make any concessions there really.

BM: Owl is very likely to be put in the Young Adult Section of Public Libraries but do you think as a group these people actually exist? How much guidance do you think children should be given over their reading?

JO: Categorising books is always a problem. I think the YA section is really only useful as a signal that content and language are intended for a more sophisticated or mature reader than your average pre-high school kid. I don’t believe children need guiding as such in their choice of reading – unless they ask. I read everything I could lay my hands on from a very early age. Children will only take from any book what triggers a response in them – the rest will pass them by. It can mean of course that they miss the real substance of a book if they are ‘too young for it’ – and there are books I read far too young, and I saw my kids do the same. But there are always other wonderful books coming up, so it’s no big deal really. Anyway, from the opposite end of the scale, as an adult I have no problems with selecting books for myself to read from the YA section – some great stuff there.

BM: Your new role as a freelance writer interpreting natural science and history can’t leave many uncommitted moments. How difficult is it for you to make time to write? Are you a disciplined person?

JO: I’m still inclined to make my contract writing a priority, partly because I enjoy it and it allows me to put all my experience and training to useful effect – and of course I need the money. But also partly because I always have this feeling that it really doesn’t matter if I don’t write another book – there are plenty of good writers for children out there doing their thing. I’m still pretty unsure of myself as a writer, not use of words – I know I can do that well, it’s more not being sure my stories need telling. I do feel like a beginner again, and the self-doubt that was always there is perhaps inevitably pretty strong after so long away from writing. A lot depends on Owl. It’s that self-doubt that makes it hard for me to sit down and write too – I’m disciplined enough, having worked from home most of my working life. Once I’m into a book, it’s better – I enjoy exploring where the story is taking me.

BM: How did you originally become involved in writing?

JO: Becoming involved in writing originally was chance and opportunity – space and time suddenly appeared in my life, and I needed to fill it productively. I was unemployed, home with a young baby, two children at primary school, and have never been good at not having mental occupation. I hadn’t ever planned on writing, or not consciously. It just seemed like it would be fun to have a go.

BM: Do you have any general opinions about publishing for children in New Zealand? What are your thoughts on placing New Zealand books for children in an international market?

JO: I’ve touched on this already – so many good NZ writers out there now. In the time I wasn’t writing and wasn’t really reading children’s stuff either, all these amazing books were appearing. There were about 10 of us actively writing in the eighties – now there are more than a hundred I think. Not all of these writers draw specifically on their NZ origins in their stories, and that’s fine. But I do think it’s important to have stories that grow out of the NZ experience and reflect our culture, our place – how else do we know who we are? For that reason, I am sad when I hear about writers being asked to remove NZ reference and language from their books for international markets. Surely children like to read about ‘elsewhere’ – if all the books are similar in style and setting and language, where is the richness, the differences that colour our world and make it interesting? What rubbish that children ‘won’t understand’ the references – when did it ever stop us reading foreign stuff – all those generations when we had very few specifically NZ children’s books? I do think this is a publishers’ perception rather than a reality. One of my hobby horses – and not just because it prevented my books being taken up by overseas publishers.

Joanna Orwin on Cultural collisions – writing stories with Maori content

A talk given at the INNZ workshop Christchurch 2012

Story tellers who use elements of other cultures can be accused of cultural misappropriation. As a Pakeha writer of stories based on New Zealand history, I believe that to exclude relevant Maori perspectives from such stories is the more heinous crime –– a form of cultural segregation that diminishes the significance of those perspectives. Sharing stories is the best way I know to improve understanding and tolerance of different points of view. But it’s easier said than done. This article describes my experiences in writing Collision, a novel based on French explorer Marion du Fresne’s sojourn in the Bay of Islands in 1772.

Who do you approach when needing Maori content? Finding the right person with both the knowledge and the authority to share it is crucial. This is more of a problem for an individual Pakeha writer with a one-off project than for people in an organisation that already has access to Maori advisors, and the project is part of building long-term relationships. If you talk to the wrong person, doors will shut, and stay shut. Fortunately, I already had appropriate connections in the Bay of Islands from an earlier project [kauri: witness to a nation’s history].

When do you involve your informant? Information from any one source will be skewed –– the nature of all history. So first, I read everything published I could trace, including C19th century Maori manuscripts. This also gave me the chance to ascertain what source material my informant did not already have in her extensive library. Copies went with me as koha –– a small way of reciprocating her gift of time and knowledge. Apparently, no other Pakeha researcher had ever shared information with her, just taken hers.

How do you get the information? I soon learnt that in the Maori world, direct questions find no answers. Nor will you be told if you get things wrong. Over nearly two weeks, my informant put fascinating material in front of me and pointed me in various directions –– none directly relevant. Despite my growing frustration, she knew better than me, and I was able to build much of what I did learn into the fictional C19th Maori manuscript that was how I finally told the Maori side of the story. That choice too was the result of sensing my initial plan for a contemporary Maori narrator to match the French one was fraught with political difficulties.

What were the rewards? When I eventually sent my informant the draft fictional Maori manuscript, the door opened. For a month, we enjoyed a stimulating two-way e-mail correspondence. Apparently I had achieved the first accurate telling of a Maori perspective on events in the Bay of Islands in 1772, and in so doing had won her trust. The time and effort in the end yielded treasures I could not have accessed any other way.

It is possible to use Maori information from a wide range of published sources, so some reputable Pakeha writers argue that it is unnecessary to take time to build trust and respect kanohi ki kanohi, or to ask permission. Once I might have agreed, but times have changed. Sharing our stories and the telling of them enriches the end result. The road is often rough, but the more we tread it together, the smoother it will become.

Joanna Orwin for College of Education University of Otago newsletter 2009

Grey skies, wind and rain through most of a bitterly cold May, June and July – some say this has been the worst winter on record (and not just in Dunedin). Despite donning merino long johns and still struggling to keep warm enough in the 100-year-old Robert Lord Writers Cottage, when I look back on my 6 months in Dunedin, I’ll remember only warmth – the warmth of the welcome I’ve received and the friendship of the people I’ve met. I have hugely enjoyed my time here.

My waistline is suffering from over-indulgence at cafes during numerous coffee and lunch sessions, but my head is full of stimulating conversation, good music and live theatre. I’ve been unable to resist the excellent second-hand book shops as well as the University Book Shop in its inviting wood-paneled old building, so the one box of books I brought with me has grown to the three I’ll take away with me. I’ve tamed the coal range in the Cottage so have indulged in long, piping hot showers as well as cooking most of my meals on its hot plates and in its oven. I’ve roamed the hills and coastlines surrounding the city while enjoying the comradeship of a bunch of fit and enthusiastic local trampers, and I’ve strolled along now-familiar streets packed with interesting architecture and historic houses. In between times I’ve explored every nook and cranny of the Botanic Gardens and the University campus, watching the changing seasons and the glorious spring blossoming of ancient flowering trees. I have bellbirds and tui singing in the small kowhai trees at the Cottage.

And this is just the fun stuff. My time here has been productive beyond all my expectations of what I might accomplish. With such easy access to the wonderful University library and printing/photocopying facilities, I have completed all the research I planned for the project I’ve been working on – a post-apocalyptic story for teenagers set several hundred years after cataclysmic volcanic eruptions on the Pacific Rim. I’m loosely basing this three-part story on pre-history Polynesian settlement patterns and life styles, using them to explore what leads isolated island societies to success or failure and the role of religious and political power in that process – Easter Island history being the trigger for this project. During the 6 months of the Residency, I have finished a complete draft of the first part of this story – the fastest I’ve ever written a 62,000-word novel.

This in itself is a measure of the benefits of this Writer’s Residency. Despite the delightful diversions I’ve outlined, the real focus of my time here has been writing. Having financial freedom and continuity of time and effort to spend on one project has meant my writing has progressed without any disruptive setbacks (apart from my usual need to rewrite several times the first five or six chapters while I found my way into the story and developed the characters). As a result, although normally when I’m revising, my scientific editing background gives me a ruthless eye and a trigger finger on the delete button, I am finding that this completed draft needs fine-tuning only, no major rewrites. [This novel was published by HarperCollins as Sacrifice 2011]

As well as being able to focus on my own writing, I’ve contributed in small ways to programmes at the College of Education and the wider University. Although finding the prospect nerve-wracking in anticipation, I’ve enjoyed the sessions talking to students and staff. I also had the pleasure of being able to launch my latest novel Collision in Dunedin towards the end of the Residency, a successful and well-attended event at the University Book Shop.

I’ll miss Dunedin, its environment and the people I’ve met here, but will go home to Christchurch feeling I’ve made the most of the opportunities provided by being awarded the 2009 Children’s Writer in Residence.

Long-awaited and Compelling: The Return of Joanna Orwin

Joanna Orwin? Who? Winner of the senior novel award 2002? But Owl’s her first novel, isn’t it? Not so, though anyone familiar with only recent New Zealand books might think it is. However, after fourteen years Owl marks Orwin’s long-awaited return to children’s novels. It shares with her previous novels, but more compellingly, the hallmarks of quality and integrity, employing convincing detail to underpin leaps of imagination and weaving contemporary life through legendary demands. As before, Orwin endows her developing teenage characters with physical and mental stamina in an overall positive, co-operative approach to life. And the power of the landscape again intensifies her storytelling with special value for New Zealand readers.

Orwin’s novels leading up to Owl show an interesting pattern of development. She began with Ihaka and the Summer Wandering (1982) and Ihaka and the Prophecy (1984; short-listed for the Book of the Year in 1985), in which she portrays a young Maori boy in moa-hunting times maturing into a stone-carver and tohunga. These novels originated from a passion for reading and from friendship with a boy companion:

I grew up in a family with a busy doctor as father and a mother who devoted her time to looking after him. I shared much of my early childhood with the son of close family friends, the brother I didn't have. Both bookish, we combined an insatiable devouring of encyclopaedias, books on explorers, adventurers and seafaring with our own semi-adventures - building huts and rafts (which never floated for long), making dams, exploring the semi-wild fringes of Nelson (mudflat, river, hills, bush). A lot of those activities were shared, until we were about 11 when it was no longer cool for boys to have girls as friends. I can still remember the sense of loss and exclusion - tempered by not wanting to be a part of the more risky activities he and his new group of friends were involved in (making gunpowder, serious tunnelling into the river bank). I do think those years were some of the happiest of my life, and they certainly explain why I like writing about boys - I really wanted to be a boy back then. ‘Normal’ girls didn't have anything like so much fun.

More particularly, the Ihaka duo grew out of an extended twist on what is familiar to many New Zealanders: a sharpened perception of local surroundings through overseas experience:

A year in the UK in Rosemary Sutcliff country awakened my awareness of how powerful landscape is [in] its holding of cultural memory and history [...].Time on my hands with a young baby, two kids at school and no job after our return to New Zealand [let me] try my hand at creating an aka-Sutcliff story for New Zealand kids that captured something of our pre-history. [It was]instinctive to use a landscape that had always held something of that almost tangible atmosphere of past peoples for me - Delaware Bay, just out of Nelson - and an abiding image of the moahunter quarry on the Whangamoa Hill that I'd been taken to see by my godmother shortly after its re-discovery when I was 12 or so.

In addition, Orwin’s research was thorough and extensive:

I started with Roger Duff’s The moa-hunter period of Maori culture, then went on to read every archaeological and anthropological paper I could find in the New Zealand room at the library, using the research skills familiar from compiling an annotated bibliography of New Zealand ecology as one of my first jobs for the Forest Service. I haunted the back rooms of museums here and in Nelson, badgering the staff for information, [broadening] this with Elsdon Best, Peter Buck, etc, on later Maori culture, works on Maori legends and waiata (Alpers in particular, and Apirana Ngata’s Nga Moteatea). I started writing when the characters I was keeping in my mind had developed enough 'trappings' to become real to me. All great fun and fascinating.

Obviously, Orwin’s training and interests stood her in good stead. She went on to write The Guardian of the Land (1985) and Watcher in the Forest (1987), the former the winning Book of the Year in 1986, the latter shortlisted for the same award in 1988. Both books weave contemporary life through historical events, dealing with racial relationships and with the need to right wrongs done in the past. Both use fantasy elements in time-slips or visions to increase the understanding and motivation of the maturing protagonists. Both draw hugely on the power of the landscape to intensify experiences. In Watcher ... in particular, set in the Lewis Pass area, Canterbury, the mountain/lake landscape evokes a majestic scale through storm and earthquake to underline the spiritual importance of the protagonists’ mission. And in both novels, friendship and cooperation strengthen bonds between Maori and Pakeha. In The Guardian ... David and Rua find and return to the tribe the pendant taken in the past from the Kaikoura chief by an unscrupulous whaler. In Watcher ... Jen and her siblings restore the stolen greenstone to the carver’s cave so that his soul may depart in peace. Not that Orwin intended to convey a deliberate message; she is far too good a story-teller to endanger narrative drive:

The solution by cooperation thing [was] not something I consciously built into my stories, but equally obviously [it’s] something I believe in as the way to deal with problems. I've never seen coercion, power play, or manipulation work effectively for long-term solutions to anything.

Though Orwin declares she likes creating boy protagonists and does so in four of her five novels, she chooses a girl in Watcher ... and in her one picture book, The Tar Dragon.

For Watcher ... [...] I thought it was perhaps time I tried a female character (certainly in response to adverse comment about absence of girl characters in my stories), but mainly because the approach and content required it - dream sequence and sensitivity to atmosphere seemed more female, and of course, the return of the greenstone required an element of the removal of tapu (not that I state this as such in the book) - a female role. The Tar Dragon is simply an autobiographic story - this happened to me as a 6-7 year old.

So why the long gap - apart from the picture book - between Watcher ...and Owl? Orwin speaks candidly of the debilitating consequences of frustrations and fears - many writers’ demons: lack of time for a busy mother and part-time science editor, lack of publisher support, and family bereavements:

I felt very isolated as a writer and the publishing climate of the time meant I wasn't sure I had my publisher's support, despite my previous book The Guardian ... winning the children's book award in '86. Combine that with low sales and some indication from some quarters that as a Pakeha I wasn't a fit person to be writing such stories (this never came from Maori sources), I put it all in the 'too hard' basket for the time being. It meant I didn't have the confidence or energy to tackle the story that eventually became Owl. At the time I had vague plans of leaving paid work in 1990 when my youngest started high school and trying again. It wasn't to be. First my mother died, then two years later, [husband] Don died (in 1989) - plans for a return to writing seemed both self-indulgent and unimportant. At the same time Oxford abandoned the stock of all my books - reinforcing an innate feeling that Orwin books weren't wanted anyway. Family was all-important and I concentrated on my kids and earning a living until they were more-or-less financially independent - two through 5 years of university and Kate almost so. But I was writing other stuff during those years - all non-fiction. I wrote a lot of trade articles on forest research and related topics - and thoroughly enjoyed it; and through the Maori language and literature courses I was doing at university, I became involved in the oral history project that eventually became Syd Cormack’s published memoirs. Certainly by the end of that time I was feeling an urge to try fiction again - and eventually decided I could afford to take the gamble, leaving Landcare Research in 1998 to write Owl and support myself with contract writing (panels and brochures on natural history, Maori and early European history).

Again, Orwin’s interest in Maori-Pakeha relationships and in the importance of cooperation characterises her latest novel set on a high-country sheep farm in the harsh, brooding, dangerous mountain landscape of Canterbury during severe winter storms. When Hamish, alias Owl, discovers old Maori cave drawings and removes a protection stone from the kete he finds nearby, he reactivates an ancient legend in which a pair of giant, fierce, predatory eagles (now extinct) swoop down on defenceless sheep and lambs trapped in the snow, their slaughter hastening the approaching financial disaster for the family begun previously with the death of Hamish’s father and worsened by Hamish’s mother’s depression. Orwin is on record as saying that she was indirectly influenced by Alan Garner’s The Owl Service (1967), read twenty years earlier, and the parallels are obvious. True, her gritty three teenagers and their part-Maori helper are not involved in inter-generational love triangles, but the power of the landscape to hold ancient dramas until the time is right for reactivation is as much a part of Orwin’s novel as it is of Garner’s - and, too, of Margaret Mahy’s The Tricksters. Orwin, however, sees her legend as a metaphor for the challenge of facing and accepting change, on both the family scale and that of broader Maori-Pakeha relationships. With authentic dialogue, fully rounded characters, and natural sibling hassle yet obliging responses, the family works through the destruction of the eagles and the return of the land to the local Maori.

Orwin’s use of legend is unusual in New Zealand children’s fiction. Unlike English writers who want to draw on established legends such as the Arthurian cycle, New Zealand writers haven’t had the groundwork done for them; they must create new stories or build on Maori legends not widely known, as Orwin does:

The legend as told in the kuia’s voice while they’re working out what they have to do is the 'true' legend - the male, female, and chicks sequence. The nest on the mountain (Torlesse) is also true to one version, and the trap needing to be in a hollow. The rock shelter and its cave drawings and their association with the legend are entirely mine, though the type of drawing - birdman figures, etc, are real. It's a Canterbury legend, though there is an Otago version widely known amongst South Island Maori, but not that well known to the general public.

As for the future, Orwin still has to face some of her old demons:

I'm still fighting the gut feeling that the stories I write or want to write don't matter. I know I'm a good writer, I don't know that the stories I want to write are of interest to anyone else - and that is a barrier. I still give priority to my contract stuff, so still have the problem of not getting long enough periods on the writing, though at least I have the ability if not the will to change that now.

Winning the Senior Fiction award for 2002 must surely encourage Orwin to believe more firmly in herself. Maybe it’s her turn for a Creative New Zealand writing grant to give her the time she feels she desperately needs. For it is certain that New Zealanders need Orwin’s books for their integrity, for their compelling storylines portraying maturing teenagers, for co-operation benefiting Maori and Pakeha, and for the power of the landscape to help define who we are and what experiences we face.

Joanna Orwin on the Canterbury earthquakes, for Landfall 222, spring 2011 - Living Heart

Early spring. Tracery of still-bare branches against a big clear sky. Suburban streets lined with the pink and white haze of emerging blossom. Drifts of daffodils forming amber pools under the tall trees of Hagley Park. Crisp frosts followed by balmy days. Gleam of snow on the distant alps. Signs of renewed life after the dreary dark days of a southern winter. After 4 September 2010, such familiar scenes were both surreal and reassuring.

Rudely awoken before dawn that day to endure several ice-cold hours of continuing darkness amidst repeated violent shaking, when I took my first tentative steps outside, there was my garden, strangely unchanged. Although the birds remained eerily silent for some time, winter roses continued to nod their subtle heads, the first blooms glowed on rhododendrons, and small bulbs created spots of intense blue, gold and purple. Over the next few weeks, my garden provided solace and calm on each return from helping to shovel grey sludge. I spent days pottering amongst my treasured plants, finding the approaching rumbles and frequent shaking less alarming outside than inside a house that now felt insecure despite suffering only minor cosmetic damage. Throughout the year of aftershocks since then, it is my garden more than anything else, the passage of the passing seasons, that has provided me with the reassurance of normality, restored my fragile nerves, and kept me sane.

But I am one of the lucky ones, living in the north-west without liquefaction. Those in the hard-hit eastern suburbs, in Kaiapoi, and the outlying northern coastal settlements are not so fortunate. So many gardens have been repeatedly inundated by the silt of liquefaction, gardens laboured over with love destroyed in heartbreaking seconds. Now, in September 2011, a year on, with the expected confirmation that so much of these areas has been zoned red, people are not only facing the loss of their homes, but the loss of their gardens. Whether well-established quarter-acres in old suburbs or newly planted plots in modern subdivisions, these privately owned gardens are not only the pride and joy of their owners, old and young, but also major contributors to Christchurch’s reputation as a garden city.

Although much of the focus post-quake has inevitably been on our built environment, including the lamented loss of many fine heritage buildings, little attention has been paid to the impending, equally devastating, loss of heritage trees and gardens with their associated stories. In particular, many established gardens along the banks of the Avon River – some of them well-known, all of them part of Christchurch’s identity and history – will now be abandoned. At present, their predicted future is dire. Obliteration by bulldozer, along with the houses.

We should not turn our backs on them so carelessly. Gardener and commentator Diana Madgin, whose own, beloved, decades-old garden is one of those condemned, has suggested that they could be incorporated in the proposed riverfront park that will be developed along the Avon. This is an idea that is gaining a lot of support. We can only hope that it is taken up formally by the city planners so that at least some elements of these gardens are preserved and included in the final central city plan.

For Christchurch residents and visitors alike, it is the city’s major public green space that is providing much needed continuity. For nearly 150 years, the vast, tree-lined spaces of Hagley Park and densely planted Botanic Gardens have served as the living green heart of Christchurch, at present a poignant contrast to the same-sized black hole that has been the city centre since the tragedy of the second major quake in February. An equal amount of land was earmarked for the park by the Canterbury settlement surveyors to that set out for the CBD, with Hagley Park being formally reserved in 1855. Transformation of tussock-clad sand dunes and old shingle river beds into the adjacent Botanic Gardens began in 1863, when the first English oak was planted. As well as converting the natural landscape into formal gardens, successive curators and gardeners – all avid tree planters – set about establishing what was to become one of the best collections of heritage trees in New Zealand, containing both exotic and native specimens. This was a process that has not stopped since.

Within days of the September quake, both residents and visitors sought solace in the Gardens. The dedicated staff, some of them immediately back at work after each major aftershock despite having damaged homes to deal with, have ensured that the Gardens remain a safe and peaceful haven. After the first quake, shocked people came in a steady trickle to wander the paths, sit in the sun, or reach out and touch the reassuring trunks of the magnificent mature trees with their steadfast message of endurance. Each school holidays, the Gardens are abuzz with excited children participating in imaginative and innovative programmes being run by the staff – in the July winter break alone, 7000 people, children with their parents, enjoyed a fantasy trail that led them to the grand finale of a host of gnomes hidden amongst the greenery of the fern house. The normal work of the Gardens has continued without pause, the planned programme of clearing and planting, watering and mulching taking its course alongside the repair of damage and removal of trees made unstable by the quakes or the heavy snow falls experienced in July and August.

For many of us throughout this year of aftershocks and uncertainty, it is the Botanic Gardens and the recreational spaces of Hagley Park that are giving us real hope for the future of our city and helping us to heal our disrupted lives.

Joanna Orwin

September 2011

New Zealand writer Joanna Orwin grew up in Nelson. Regular family holidays at nearby Lake Rotoiti instilled the interest in New Zealand’s natural landscapes that feature in all her books, both fiction and non-fiction. She has lived in Christchurch all her adult life.

A BSc (Hons) in botany led to research work as an ecologist with the Forest Research Institute in 1967, followed by taking on the role of in-house editor. Editing in environmental sciences continued to be her paid employment until she left Landcare Research in 1998 to pursue her own writing.

In the 1980s, Joanna began writing novels for children set in New Zealand landscapes. All four novels published between 1982 and 1987 featured Maori elements, directly in the two Ihaka books and through time shift in The Guardian of the Land and Watcher in the Forest. All but her first book were short-listed for the New Zealand Children’s Book Awards, with The Guardian of the Land winning in 1986.

The death of her husband in 1989 compromised Joanna’s commitment to her writing. After Watcher was published in 1987, she did not feature in children’s book lists again until Owl was published in 2001. During her absence from the writing scene, she completed a BA started in 1963 with papers on Maori language and literature, particularly focusing on translating nineteenth century Maori texts. Since 1998, Joanna has focused on her creative writing career, supported by contract work as a consultant researcher, writer, and editor. Her most recent consultancy project was the research and writing for the exhibits in the new Visitors’ Centre for the Christchurch Botanic Gardens, completed in 2013.

Joanna was awarded the 2009 University of Otago College of Education Children’s Writer Residency. Her children’s books have continued to be short-listed for the New Zealand Children’s Book Awards, with Owl winning the Senior Fiction category in 2002. Two of her non-fiction books for adults, Four generations from Maoridom and Kauri: witness to a nation’s history, received Awards in History. Her most recently published book, Riccarton and the Deans family: history and heritage (2015) was short-listed for the NZ Heritage Book Awards 2016. An updated and revised hardback edition of Kauri was published in 2019, and Joanna released her second historical novel for adults, Shifting Currents, in July 2020.

Useful links:

http://www.bookcouncil.org.nz/writers-files/

https://authors.org.nz/

https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/new-zealand-childrens-authors/

Short-listed Children's Book of the Year - 1984

Winner, Children's Book of the Year - 1986

Short-listed Children’s Book of the Year - 1988

Award in History - 1992

Senior Fiction Winner, NZ Post - 2002

Creative NZ grant - 2000

Award in History - 2003

Young Adult Finalist, NZ Post - 2005

Creative NZ grant - 2007

World Harmony Run NZ - 2008

University of Otago’s College of Education Children’s Writer in Residence - 2009

Short-listed, YA Fiction NZ Post - 2012

Short-listed NZ Heritage Book Awards - 2016